The Signal Density Problem: Why Most Meta Accounts Are Structurally Broken

How fragmented account structures quietly slow learning and destabilise performance.

Executive context

Many Meta accounts are struggling not because the algorithm changed, but because their structure is incompatible with how learning now works. As Meta’s systems predict outcomes earlier in the auction, fragmented campaigns and budgets quietly destroy signal density, slow learning, and destabilise performance. This article explains why most Meta accounts are structurally broken and what growth leaders must change to restore reliable learning and decision-making.

What Most Teams Are Solving for (And Why It’s Wrong)

Most Meta accounts do not fail loudly. They fail quietly. Costs creep up, performance becomes erratic, and learning phases stretch longer than expected. Over time, teams start describing results as “volatile” or “unpredictable.”

Eventually, a familiar explanation surfaces. The algorithm changed. Automation increased. Control was taken away. This explanation is comforting because it shifts blame outward, but it is also incomplete.

What most teams are experiencing is not a platform failure. It is a structural failure. For leadership teams, this is no longer just an ads performance issue. It is a forecasting and credibility issue. When Meta account outcomes become unstable, confidence in growth planning erodes, budgets freeze, and teams lose strategic latitude. Meta did not suddenly become harder to use. It became less forgiving of systems that were never designed to learn efficiently.

The real problem most teams are not diagnosing

When Meta account performance becomes unstable, teams instinctively focus on what is most visible. These are familiar levers, and they offer the comfort of action.

Most teams respond by:

-

Reviewing creatives to look for fatigue or messaging gaps

-

Debating audiences and overlap

-

Questioning bids, placements, and attribution models

What rarely gets questioned is structure.

Specifically, how budgets, creatives, and conversion signals are distributed across the account. Modern ad platforms no longer reward precision through control. They reward learning speed. If a system cannot learn quickly, no amount of optimisation can save it.

This is where most Meta accounts quietly break.

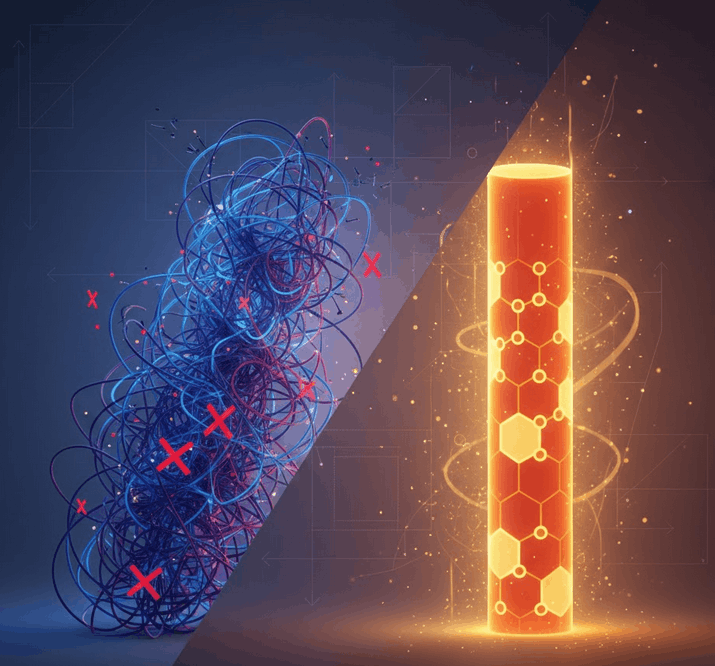

Signal density as the core constraint

Signal density is the volume of meaningful feedback a system receives relative to the number of distinct learning buckets it is forced to manage.

In practical terms:

Signal Density = Conversions ÷ Learning Buckets (ad sets, campaigns, or parallel systems)

A system with high signal density:

-

Learns quickly

-

Produces repeatable insights

-

Stabilises performance over time

A system with low signal density:

-

Learns slowly

-

Produces noisy and inconsistent data

-

Feels unpredictable even when inputs remain stable

This is not a Meta-specific concept. It applies to any learning system, whether human or algorithmic.

What makes Meta different today is that the platform assumes you will design for learning, not for control. Learning speed is inversely proportional to how fragmented your signal is. Every additional learning bucket slows convergence.

When signal is fragmented, the system is forced to guess.

When signal is concentrated, the system can converge.

This is not a technical insight.

It is a leadership constraint.

How fragmentation became the default

Most structurally broken Meta accounts were not built irresponsibly. They were built logically, step by step, over time.

A new audience is added to test a hypothesis. A separate campaign is spun up to isolate performance. Budgets are fragmented to “preserve clarity.” Each decision makes sense locally, but collectively, they produce a system that cannot learn.

Over time, this logic compounds into familiar structural patterns:

-

Multiple campaigns optimising for the same business outcome

-

Cold, warm, lookalike, and retargeting split into separate systems

-

Budget fragmentation framed as experimentation

-

Structures designed to protect reporting clarity rather than learning efficiency

These structures persist because organisations reward control.

Control feels safe. It is easy to explain in meetings and reduces short-term discomfort. Learning does the opposite. It looks messy before it looks stable and harder to defend while it is still converging.

Fragmentation feels disciplined.

In practice, it starves the system.

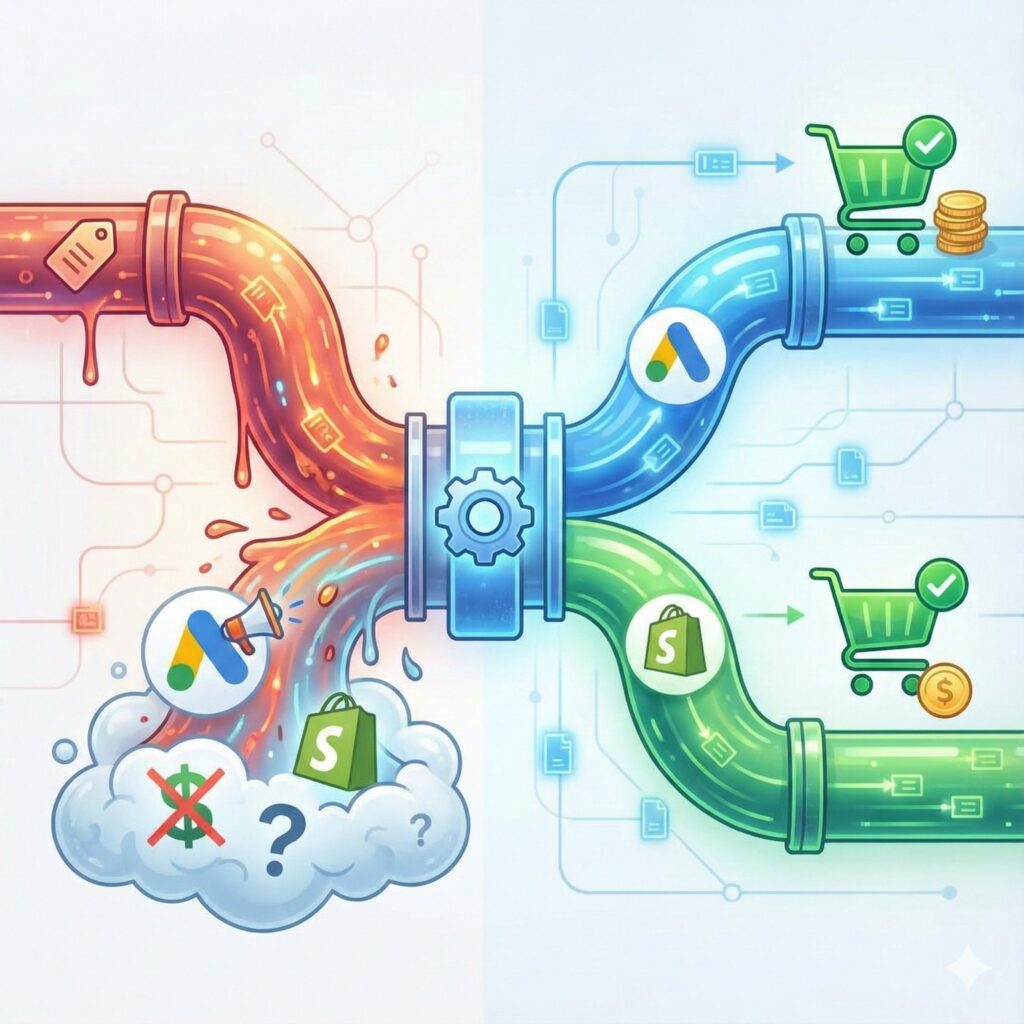

Why Andromeda surfaced the issue

Before Andromeda, manual targeting acted as a buffer. It reduced the learning burden by narrowing the problem space. When learning was slow, targeting compensated by limiting who the system had to evaluate.

With Andromeda, that buffer disappeared.

The system now predicts the outcome before an ad even enters the auction. If your signal is too weak for the AI to make a confident prediction, you do not just pay more. You do not even get to play.

This is why fragmentation suddenly became painful. As systems like Meta Advantage+ and broader CBO setups prioritise faster learning phase optimisation, fragmented ABO-style structures struggle to converge. The system cannot form confident predictions when signal is split across too many parallel learning buckets.

Andromeda did not introduce a new problem.

It removed the mechanism that was masking an old one.

The hidden costs of low signal density

Low signal density has consequences that compound over time. Some of these show up quickly at the account level, while others surface more slowly across teams and leadership.

At the Meta account level, teams typically see:

-

Higher CPMs due to inefficient auctions

-

Longer and repeated learning phases

-

Inconsistent creative evaluation

At the organisational level, the damage runs deeper:

-

False positives that get scaled prematurely

-

False negatives that get killed too early

-

Teams reacting to noise instead of patterns

-

Leadership losing confidence in the channel

As acquisition systems fragment, even downstream signals such as retention and repeat behaviour get drowned out by noisy top-of-funnel learning. Over time, trust in data erodes. Teams respond by adding more controls, which fragments signal further and slows learning even more.

Low signal density does not just waste budget.

It trains organisations to mistrust learning systems entirely.

What high signal density systems do differently

High-performing Meta accounts are not defined by superior tactics.

They are defined by superior constraints.

Instead of optimising for control or reporting neatness, they make a different set of decisions:

-

They prioritise learning speed over reporting clarity

-

They accept short-term discomfort in exchange for long-term convergence

-

They allow budget to follow response, not structure

-

They treat structure as temporary, not sacred

Just as importantly, they refuse certain behaviours.

High signal density teams refuse to protect legacy structures. They are willing to break clean reporting views, tolerate temporary ambiguity, and remove campaigns that exist only to preserve internal comfort.

They do not chase stability through restriction.

They earn stability through feedback.

The organisational blind spot

If signal density is so important, why do structurally broken Meta accounts persist?

Because signal density is difficult to sponsor.

Simplification feels risky, while complexity feels defensible. Managers prefer systems they can explain. Agencies prefer systems they can justify. Leadership often prefers predictability, even when that predictability is artificial.

Signal density itself is not hard to understand.

It is hard to defend internally, especially when early learning phases look unstable and results feel temporarily messy.

This is where many teams stall. Not because they lack insight, but because they lack organisational air cover.

Reorienting without tearing everything down

Improving signal density is not about rebuilding from scratch. It is about changing the questions leaders ask.

Most teams default to operational questions:

-

Which audience is underperforming?

-

Which campaign should we pause?

High-performing teams ask different questions:

-

Where are we fragmenting learning?

-

Which systems are competing for the same signal?

-

Are we optimising for clarity in reporting or clarity in learning?

This is not an execution problem.

It is a leadership decision problem.

The next ninety days should not be spent adding sophistication.

They should be spent removing friction from learning.

The final reframe

Modern growth is no longer about finding better audiences.

In AI-led growth, performance does not come from better optimisation. It comes from creating better environments for learning. Systems that learn quickly stabilise. Systems that cannot learn remain volatile, no matter how much effort is applied.

Most Meta accounts are not failing because the algorithm changed. They are failing because their structure is incompatible with how learning now works.

Fix the structure, and performance follows.

Look at your ad account today. Is it optimised for your control, or is it optimised for the algorithm’s learning speed? You can no longer have both.